A series of texts on Palestine

republished by an anonymous group.

Volume 2, Pamphlet 3/10 - 2025 (#27).

Original text and images first published in 2024

https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/in-tune-with-their-time

We are (re)publishing these texts to disseminate knowledge on the history and present-day struggles for justice and liberation for Palestine and the Palestinian people. We opted for publishing the texts without going through the process of seeking permission from the authors or publishers*. We believe that these texts ought to be read, circulated, and acted upon urgently as the genocidal war on Palestine continues, unabated. The publications are meant to contribute to historical and political literacy for liberation in the service of the people. What is knowledge for if not to change the world to a just place for all?

These texts are not meant to be used/ circulated for commercial purposes.

The word pamphlet originates from the 12th-century Latin love poem ‘Pamphilus, seu de Amore’. Pamphilus, or ‘concerning love’ is derived from the Greek name Πάμφιλος, meaning ‘beloved of all’. The popular poem formed a slim codex and was copied and circulated widely.

This threatening atmosphere of violence and missiles in no wayfrightens or disorients the colonized. We have seen that theirentire recent history has prepared them to ‘understand’ thesituation. Between colonial violence and the insidious violencein which the modern world is steeped, there is a kind of complicitcorrelation, a homogeneity. The colonized have adapted to thisatmosphere. For once they are in tune with their time.

Frantz Fanon,The Wretched of the Earth, 19611

There will be time to bury the dead. There will be time forweaponry. And there will be time to pass the time as we please,that this heroism may go on. Because now we are the masters oftime.

Mahmoud Darwish, Memory for Forgetfulness, 19822

Israel is a defeated project. I don’t mean this as a moral indictment. I take it to be, at this stage, quitesimply a historical fact. An Israel that has normalised its status in the world and region, rules stablyover subject populations, ceases to practice apartheid, closes its open frontier, declares borders, nolonger relies on extra-legal discretionary settler violence, and transitions out of a permanent warfooting will never happen. It is already finished. It is at best a badly frayed, but lethal, fantasy. The kind you hold onto more outof spite than genuine anticipation. In a certain but important sense–one thatneeds plain stating–we already live in a worldafterthis possibility, after Israel. This Israel is already afuture-past. The persistence of Palestinian life and its refusal to simply die and disappear has alreadyachieved this. And any vision of a noncolonial mode of cohabitation in historic Palestine must beginwith this recognition.

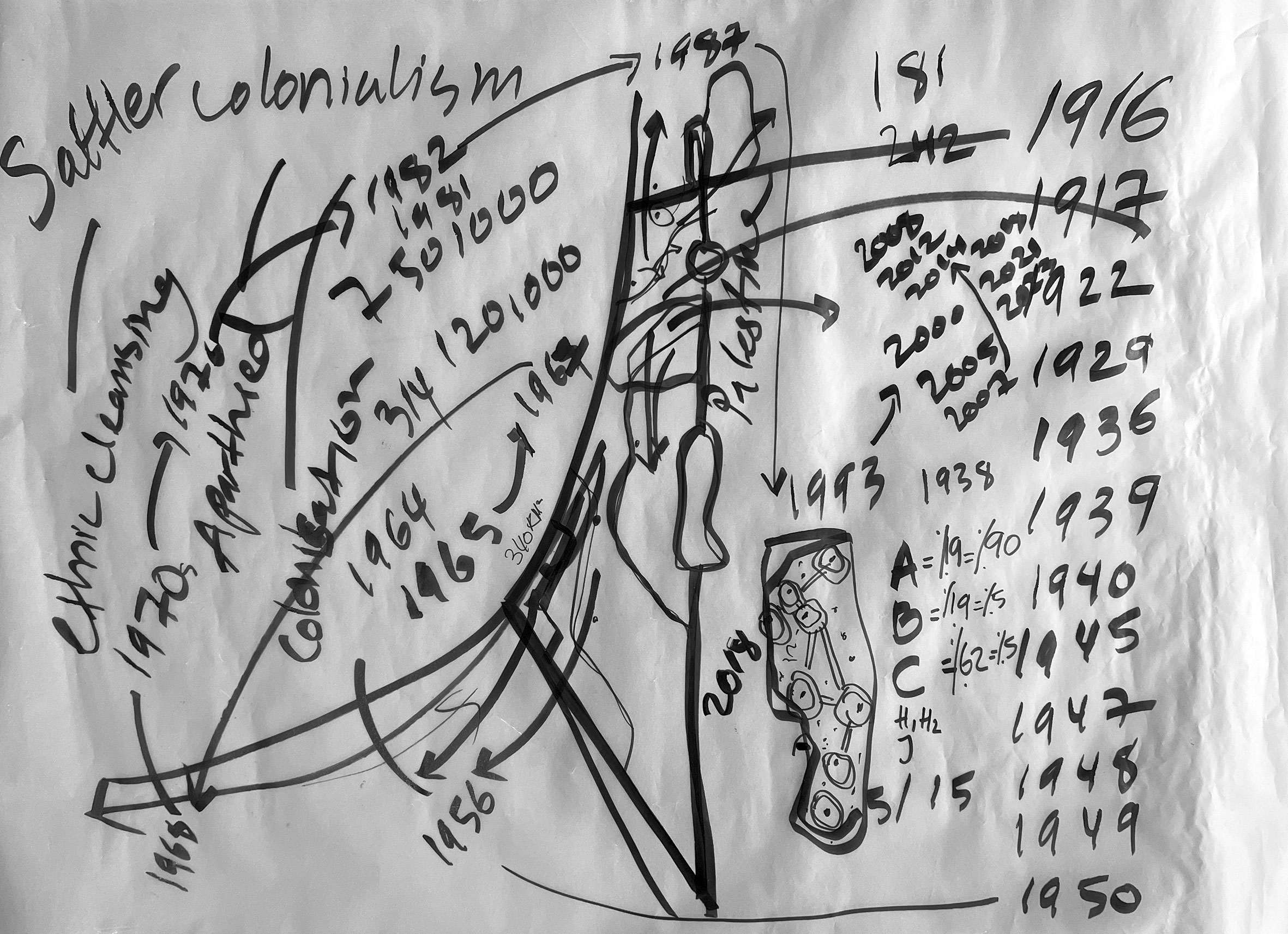

What we are living through today is Zionism’s endgame. This is not to be sanguine. Colonial endgamescan last a long time; they are almost always utterly brutal. But the brutality is as much a sign of theirdefeated denouement as much as anything else.3 Colonial endgames are defined by a diminishingrange of options and the fact that each move leads exponentially faster toward the end. Zionism’sendgame is not born simply of the Israeli project’s immanent contradictions rising to the surface. It isborn decisively out of the persistence of Palestine’s long century of anticolonial struggle that has overthe last two decades amounted to the most sustained challenge in a renewed war of nationalliberation in generations. About this we should be clear and unapologetic: the Palestinian war ofnational liberation is posing an intractable challenge to the colonial order. Zionism is not failing.Zionism is being defeated.

The headfirst charge into a frenzied genocidal campaign in Gaza can only be understood if parsed inthe full historical arc of struggle over Palestine that reaches this current inflection point. That is, this conjuncture can only be understood if it is located in the foundational impasse of the Zionist project.

Zionism is at an impasse because itis defined by the stunted drive of its conquest. It is a project thatwhen faced with a resilient arc of refusal finds itself temporally stuck, unable to transition beyond itsfoundational moment, unable to make permanent and finalise dispossession in stable regimes ofproperty and law, unable to move past the past. Political orders that cannot close their moments offoundational conquest and consign that conquest’s violence to the political unconscious arevulnerable orders. They are unsettled orders.

Nadine

Fraczkowski

Nadine

Fraczkowski

Zionism’s entire purpose, its raison d’etre, has always been the establishment of a racially pure ormajoritarian Jewish state in Palestine, and yet it finds itself today, governing and ruling over sevenmillion native Palestinian subjects–over half the population it controls–that it has no intent orability of ever absorbing as members of its national body politic. This is simply an irreduciblecontradiction. From the standpoint of the racial state, it is an immunological disaster; one that notonly meansthe state must remain formally or legally defined in racial terms (and can never transitionto the devices of liberal democratic formal equality) but also dooms it to a constant reenactment ofthe violence of conquest. In the long-term historical sense–and it is precisely this temporal senseand horizon that now imposes itself–Zionism only has two options in front of it: equality (and thusself-negation) or genocide. That it opts so clearly for genocide, underlines just how much theelimination of thePalestinians is Zionism’s master-desire, the primary object of its drive. Zionism is at an impasse because itis defined by the stunted drive of its conquest. It is a project that when faced with a resilient arc of refusal finds itself temporally stuck, unable to transition beyond itsfoundational moment, unable to make permanent and finalise dispossession in stable regimes ofproperty and law, unable to move past the past. Political orders that cannot close their moments offoundational conquest and consign that conquest’s violence to the political unconscious arevulnerable orders. They are unsettled orders.Zionism’s entire purpose, itsraison d’etre, has always been the establishment of a racially pure ormajoritarian Jewish state in Palestine, and yet it finds itself today, governing and ruling over sevenmillion native Palestinian subjects–over half the population it controls–that it has no intent orability of ever absorbing as members of its national body politic. This is simply an irreduciblecontradiction. From the standpoint of the racial state, it is an immunological disaster; one that notonly meansthe state must remain formally or legally defined in racial terms (and can never transitionto the devices of liberal democratic formal equality) but also dooms it to a constant reenactment ofthe violence of conquest. In the long-term historical sense–and it is precisely this temporal senseand horizon that now imposes itself–Zionism only has two options in front of it: equality (and thusself-negation) or genocide. That it opts so clearly for genocide, underlines just how much theelimination of thePalestinians is Zionism’s master-desire, the primary object of its drive.

From the standpoint of a stalled project of colonial settlement, genocide is neither irrational norsimply vindictive. For Zionism, it is a corrective return to a blocked pathway. It is clamoured for and felt as vitally necessary because it might be a way out of the impasse, beyond the challenge. In truth,genocide is never far from the surface in settler colonial orders. And though it is but one amongmany instruments of eliminationand the negation of indigenous peoplehood (alongside: removal,assimilation, native citizenship), historically speaking, it rises to the surface when the frontier is stillopen and contested. In Palestine, genocide, understood even within the narrow confines of the UNconvention not as the mass killing of individuals (which is the rarer case) but as the intentionaldestruction of a people’s capacity to exist, has always been the condition of possibility for politicalZionism–the Nakba was in many ways aclear case of genocide, even if it almost still cannot benamed as such.4 But that genocide-as-event returns, that it moves from latent to actualised logic, isan effect of the magnitude of the challenge posed by Palestine’s renewed war of liberation to analready stuck settler project.

It is precisely this sense of the moment as both impasse/frustration and exit/freedom for the colonialregime that explains things like the sheer volume of open genocidal incitement across both Israelisociety and state. Imean here the generalised will to discourse in the almost daily calls to flatten, towipe out, to level, to finish them; or in language that more directly indexes the immunologicalanxieties of a threatened racial order: to erase (l’mchok) or to purify/disinfect (l’tahir); or, possiblyeven more tellingly, in language that codes the incitement in calls for a completion of thefoundational conquest: ‘Nakba 2.0’. ‘rolling out the Gaza Nakba’, ‘the second war of independence’.This dual sense of impasse and exit is also there in the affective discharges so regularly displayed inIsraeli social media around images of the death and destruction in Gaza: the glee, the mockery, therancour, the cruelty, the need to humiliate; it is hard otherwise to explain the entirely excessiveamount of circulated images and videos of soldiers looting homes, wasting food, mockingly playingwith the toys of dead or displaced kids, or posing with the underwear of dead or displaced women.This generalised collapse of the repressivebarrier and inhibition in speech cannot be explainedsimply by the new permissiveness of tabooed desire; it is also an effect of the deep frustrations of thestunted libidinal drive of this project as it is checked by a people it ‘knows’ to be inferior ineverypossible way, and yet cannot somehow decisively defeat butcannow humiliate and punish.Frustrations that are marked even now in the ubiquitous retort that this is not really a genocide because, ‘if it wanted to Israel could wipe Gaza off the face of the earth’. A retort that, of course, onlybetrays how much Israel’s supporters want precisely that but are unable (for now) to achieve it.

This mixture of frustration and freedom is also the only way to understand the nature of the total,obliteratingand frenzied violence that has been meted out to Gaza. Violence that is often calledindiscriminate but is actually targeted and intentional and aimed not only at widespread destructionbut at the very basis of collective habitable life. Violence that includes the imposition of total siege,the active engineering of conditions of starvation and epidemic disease, and mass summaryexecutions.5 How else can one understand the obliteration of most of Gaza’s housing and thedemolition of entire residential blocks by the army’s engineering corpsafterfighting? Or thehundreds of two-thousand-pound bombs, some of the largest conventional munitions on earth thatkill or destroy everything within hundreds of feet, dropped not just on densely populatedneighbourhoods, but on those neighbourhoods designated as ‘safe zones’? Or the systematicdevastation of the entire public health system in Gaza, with almost every single hospital beingbesieged, invaded or bombed multiple times, and with two hospitals, including Shifa,the largest inthe Strip, effectively turned into death camps?6 Or the over 80 attacks on aid distribution?7Or thewholesale erasure of the universities, municipalities, libraries, and archives? Or the systematictargeting of Gaza’s professional classes,its doctors, medical practitioners, journalists, academics andpoets and writers? Gaza City, Palestine’s last remaining coastal city and the hub of the Strip’s life-supporting infrastructure, has been all but destroyed. This active production of the uninhabitable,this will to rubble, cannot be explained simply as momentary ‘bloodlust’ or vengeance. It has to beunderstood, historically and affectively, as the release of long pent-up exterminatory energies that inthe project’s highest moment of vulnerability feel free to p ursue the threatening object of theirdesire.

The time of initiative /Zaman al–Mubadara

Yet it would be a mistake to read the conjuncture only from the vantage point of a settler order thatfeels besieged and senses a way out. A deeperreading has to recognise that at some level this siege–the siege of the fort, the siege of the siege–is real and not just a figment of settler society’snarcissistic attachments to fears of injury and reversal. That is, it is not simply that Israel, like anycolonial order, is haunted by the prospect of the reversibility of its relations of force, but that thisreversal has over the last two decades become increasingly possible, if not likely. The Zionist regimehas managed its contradictions over the last two decades (since the collapse of the façade of aforward-moving ‘peace process’) essentially by biding time, by lethal conflict management in adrawn-out suspended temporality: siege, permanent counter-insurgency, mass arrest and detention,deepening apartheid and segregation, economic pacification and economies of humanitarian aid, andthe use of forms of native authority on the Bantustan model. In Gaza, this has been accompanied by regular bombing campaigns and massacres that were tellingly described bythe state as ‘mowing the lawn’, indexing not only the idyllic rot of suburban Americana at the heartof Israel’s self-image, or the reduction of Palestinian life to an unruly mute nature, but also theutterly banal and repetitive nature of this violence for its orchestrators–mowing the lawn issomething you do routinely and almost unthinkingly.

But the problem with biding time is that forms of resistance don’t stay still, they expand and grow indepth, penetration and sophistication with every year. The last two decades have seen the mostpronounced growth of the Palestinian liberation movement since the end of the PalestinianRevolution in the siege of Beirut in 1982, and the capture of its main political parties as the effectivefacilitators of Israeli occupation in the West Bank a decade later. This is clear if we consider the forms of resistance in their full and global gamut: civic activism, the boycott and divestment campaign,sustained forms of direct action, the growth of the Palestinian solidarity movement and the deepened ties with left parties, labour unions and movements for Black and Indigenous liberation globally, andarmed struggle in Palestine and the region.

It is the armed struggle and its rootedness in resilient forms of life thatremains illegible orunapproachable to so many contemporary observers. And yet there is no chance of grasping thisconjuncture without reading it within a historical arc of a renewed war of national liberation that hasbegun to pose insurmountable challenges to the very logic of settler colonial power in Palestine. Anarc that starts with the liberation of South Lebanon in 2000–an event of singular historicalsignificance, being the only time land was liberated from Israeli occupation without a broaderrecognition of the Israeli state–and includes the routing of the Israeli army in the 2006 War inLebanon, and the growing capacities of the Palestinian resistance in Gaza in the 2008/9, 2014 and 2021 wars. These were buttressed by the Great March of Return in 2018, a wave of popular proteststhat challenged the siege of Gaza but were met with overwhelming lethal violence, and the UnityIntifada in 2021 that saw, for the first time in a generation, simultaneous mobilisation in every partof historic Palestine. The Unity Intifada was also the cue for a renewed organisation of the armedresistance in the West Bank into self-defense zones around the major refugee camps. If the settlercolonial project has in this period sought to close time in what a senior Israeli political advisor calledin 2004 a formaldehyde solution that would ‘freeze the political process’,8 resistance factions havesought to make and open time, to set its rhythms and tempos, in what they call ‘the time ofinitiative’.

Yet there remains, even among those of us dedicated to the liberation of all peoples in historic Palestine, a certain incapacity or unreadiness to read this historical arc, to recognise its historicity.An incapacity that stems from, on the one hand, a misunderstanding or aforgetting of what anticolonial national liberation wars are about, such that we are often told, in ways that internalise amythology of Israeli military supremacy, that armed struggle here is futile, counterproductive, or atbest symbolic. And on the other, an incapacity stemming from the capture of our grammars in liberalpolitics of respectability and recognition that are fundamentally incapable of processing anticolonialpolitical violence in anything other than flat moral frames that invariably privilege state power andreify the legal categories of colonial history.9 Here armed struggle is read only at the point of itstransgression of a moral limit, and we end up with a kind of performative moral disavowal that foldsentire anticolonial struggles intothe pathologies of sadism and vengeance (only a short step awayfrom the language of ‘barbarism’ and ‘savagery’). This incapacity dogs large sections of a global leftseemingly unable to do its own revolutionary histories any justice in the present.

These are both serious mistakes. The power of anticolonial national liberation war is not in any finaldecisive confrontation. There is rarely a final battle or a storming of the palace. It is about theincremental upending of colonial power’s modalities of rule; its temporality is the long durée and itis never simply a question of material arithmetic. It is always about the opening ofpoliticalpossibilitythrough overturning relations of force–it is as such a fundamentally different logic of war togenocidal colonial war.10 But here we need to understand the particularity of colonial power to graspthe stakes. The most primary organising logic in colonial order is separation. This separation is notsimply physical or sp atial. It is ontological and psycho-affective. It is a separation between subjectand object, between the living body and the ‘body-things’ around it.11 Colonialism, then, takes theentangled intimacies, the dependencies on native bodies, labour, land, energies and presences, andtransforms them into separations and a refusal of mutuality or any kind of commonness.

The exercise of colonial domination in turn is premised most fundamentally on the logic of non-reciprocity. It is an ability to wage constant penetrative violence into native society without the coreof colonial life being touched, without any kind of response in kind. Its essence is not simply that it israw and arbitrary, but that it is untouchable. This is how it dehumanises, because it refuses any kindof mutuality at the verypoint of intimacy, precisely where it intrudes deepest into bodily integrity.

Essentially, in the tactile terms through which colonial power understands and imposes itself, it isthe ability to touch and not be touched in return. In Algeria, it was precisely this logic that connectedthe systematic torture regime with the push to unveil Algerian women; both were understood as partof counter-insurgent and civilising practices that sought to touch the depth of the intimateinteriorities of the indigenous–corporal, psychic, domestic, familial–from a position thatforeclosed any touch in return.

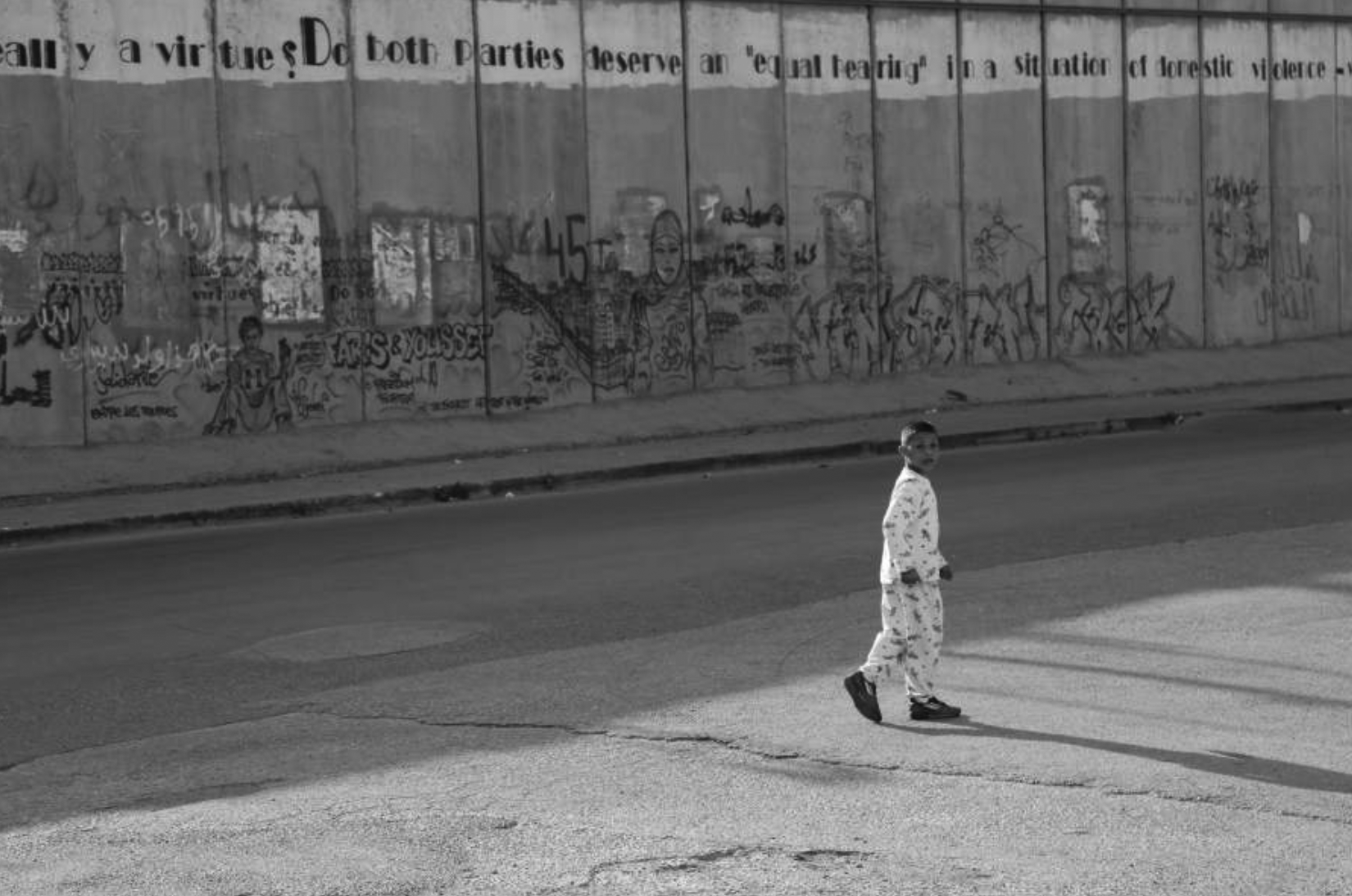

Nadine Fraczkowski

Nadine Fraczkowski

In a settler order, this untouchability has to extend to the social body as a whole. The body of thesettler and the settler body politic are co-constituted in theviolence of immunisation. And what wecan think of as the settler social contract is built precisely on this (non)relation: a core of settler goodlife in the interior that remains untouched even as the elastic colonial frontier is a space of totalviolence and ruination. Gaza as a concentration camp of dispossessed refugees that can be killed atwill is the unsaid condition of Tel Aviv as the laid-back global city of Bauhaus architecture and nightlife. But the structure only works if the regime of violence is unquestionable and unconditional.

This unconditional non-reciprocity is why for colonial order, every act of resistance, armed or not, isexperienced as violent.Because every act of resistance questions this divide between the untouchablesuper-human and the disposable sub-human (in Fanon’s terms, it mutually humanises). Colonialviolence, in turn, always has to be entirely excessive. All the wrangling about proportionality bypeople still invested in international law misses the point entirely. When challenged, colonial powerhas no choice but to be totally disproportionate. Ithasto carpet bomb neighbourhoods. Not for anymilitary reason, but because it has to constantly strive to re-establish non-reciprocity. This is whythe Israeli state understands the restoring of deterrence as an exercise in destruction. It measures itspolitical achievements in scales of rubble. It expresses its political aesthetic in the dissemination ofalmost sublime images of ruination. ‘Gaza’ as a lesson in total obliteration has to be mediatised anddisplayed on every screen. The scale and reach of destruction has to be so severe, so total, and sovisible that it reimposes the fact ofthe untouchability of the colonial sovereign in the veryconsciousness of the objects of its violence. The declared aim of many of Israel’s bombing campaignsin Gaza of ‘restoring quiet’ is exactly a euphemism for this non-reciprocity–the periods of ‘quiet’ arewhen the colonial state can kill, imprison, dispossess and displace at will without riposte, withoutrelations in kind.

The last twenty years of struggle have challenged this logic, even upended it in places. What has beenachieved in Gaza alone has been immense. A refugee people driven from their homes, encamped,militarily occupied for decades and entirely besieged in a tiny strip of flat coastal land without asingle mountain or valley, without jungle or forest, and pummeled routinely from the air, have beenable to puncture the skies and subterranean depths of a nuclear-armed garrison state. In a very realway, Gaza has in moments reversed the logic of the siege. They have taken the very munitionsdropped on their homes and turned them into a capacity for indigenous weapons-making and self-defense–when some say that in anticolonial struggle ‘every bullet is a bullet returned’, in Gaza thisis meant quite literally. In otherwords, they have institutionalised a base of cumulative indigenousknowledge and organisational capacity. When in the early days of the siege, the resistance factionsfired rockets that were by all accounts dubbed ‘primitive,’ people rushed to point out that this did notwarrant the intensity of the Israeli bombardment, that the rockets were effectively a kind of‘fireworks’ and best understood as ‘symbolic’. This missed the point. The colonial regime understoodit much more clearly: even the smallest prospect of an indigenous capacity to develop militarytechnology, no matter how ‘primitive’, is a threat to the logic of non-reciprocity.

These are the capacities defining the terms of battle today. Penned in entirely by an almost totalblockade on all sidesand without a single inch of territorial depth or rear supply lines, thePalestinian resistance has nonetheless developed an ability to confront and repel the armouredinvading columns of one of the most equipped and ruthless armies in the world, over months of warfare. It is hard to find any historical precedent for what the resistance in Gaza has so farwithstood and achieved. The Algerians had their supply lines through Bourguiba’s Tunisia and the Atlas Mountains of the interior; the Vietnamese had Maoist China and Cambodia and acres of densejungle. The Palestinians in Gaza have no territorial rear depth at all but their own resilience andingenuity. Regardless of what happens, it is unquestionable to my mind that the battles wagedagainst this genocidewill eventually be recognised historically up there with the great feats ofanticolonial history, with the battle at Dien Bien Phu or, for that matter, with the Battle of Bint Jbeilin the 2006 War in Lebanon, even if we still don’t quite have the languageto talk about it as such.

Yet there is no final battle here. No analogue to the fall of Saigon or the storming of Santa Clara is onthe horizon. Palestinians can never muster anywhere near the magnitudes of violence the colonialstate has at its disposal. But what they can do is refuse the order of colonial non-reciprocity. Theycan open and make time in a war of national liberation that denies the settler order its transitionbeyond the impasse. And here it bears reminding that the bedrock of any war ofnational liberation isordinary people’s capacity to keep rejecting the terms of defeat and insisting on life at all costs. Thisinsistence is there in the mother who buries her dead child in a mass grave and in the same momentdeclares that she won’t be moving anywhere; it’s there in the image of a young man pulled out fromthe rubble, face barely discernible under the grey cover of dust, taken out on a stretcher, whosomehow finds the strength to sit up and throw up a victory sign; it’s there in the doctors who refuseto leave their patients even as inevitable death encroaches; it’s there in the elderly man who returnsto inhabit the ruin of his home in a makeshift tarp tent so that he can search for the bodies of hischildren and grandchildren beneath therubble. In the spring of 2024, the Israeli army re-invadedareas in the north of Gaza it had claimed it had clearednotbecause the resistance factions remainedstanding, but primarily because people insisted on returning to inhabit the ruins. This insistence onhabitable life and its ordinary rhythms–that is, the refusal of the wasteland Zionism has alwayssought to engender in/as Palestine–is the basis of the broader challenge to the settler regime.There’s nothing to romanticise in this; the point is not to fold it into some image of sacrificialheroism. We know better than most that images of selfless muscular armed insurgency are deficient. They’ve let us down before. The grief is immeasurable, and nothing can fold it back onto a symbolicplane. But to rem ove this grief from the temporality of a war of liberation is to remove it frompolitical meaning entirely, to render it in the only language liberalism will allow: a strictly personalinjury. Palestinian political community, by contrast, has always–out of sheer necessity but withpolitical effects–hinged on its capacity to turn grief into defiance.12

These are forms of struggle entirely illegible to most of the liberal-left in the west. And yet so muchof the contemporary advocacy for Palestine remains premised on the notion that the Palestinianstruggle for liberation will succeed if only we appeal to certain conventions of recognition orlegitimacy in the west. This misreading should have been the first victim of this genocidal war. Theissueis nothowwe make or articulate our demands for freedom; it is that the very demand forPalestinian freedom is fundamentally objectionable.13 There are no politics of persuasion that willchange that. Even in our mass death, our humanity is denied; evenas nameless numbers, we aresubject to suspicion. This humanity is constitutively exclusive of us and always has been. It is notsimply that our life is valued differently, but that it is in fact incommensurate with value entirely.There are no performances of racial innocence, no choruses of condemnation that are going to buymembership into the club. At best, the liberal-left formation in the west might see Palestinians asrighteous victims, but never as historical actors capable of and justified in waging a war of nationalliberation. The allies we have won, we have won not by appealing for recognition, but by refusing toroll over and die, by situating our struggle, and that struggle’s principles, within the global historiesand inheritances of revolutionary anticolonialism.

None of this is to skirt over the questions of the ethical limits of anticolonial violence. Nor to implythat these limits haven’t been breached in the history of Palestinian anticolonialism, or indeed that they weren’t breached in the al-Aqsa Flood operation on October 7th. Less still that these breachesshould not be reckoned with and criticised. Palestinians have long thought about and grappled withthese questions, not as an exercise in publicity, but as part of their own political dialogue. Becausenowhere do the colonised owe these limits to their colonisers, or the editors of western journals, orthe mythic object that is the international community. The colonised owe it to themselves, and onlyto themselves; they owe it to thehorizons of futurity and cohabitation their struggle will perform, tothe world their children will inherit.

Fanon’s plea at the end ofThe Wretched of the Earthto ‘…leave this Europe which never stops talkingof man yet massacres him at every one of its street corners, at every corner of the world’,14 has neverbeen more urgent. It has also never been more achievable. Israel is the regional outpost of animperial order that is reeling. Yemen, one of the poorest countries on earth, moves oceans and defiesempires to join the struggle. South Africa turns international law on its head, breaching theunspoken colonial boundaries around the charge of genocide.15 But more still, millions of peopleglobally are interpellated by the genocidal violence in Gaza;millions are called out by and recognisethemselves in it. They look at Gaza and see not just a hundred years of colonisation in Palestine, butthe last five hundred years of Euro-American racial colonial domination. The campaign in Gaza islike a condensed restaging of every colonial war in history, bearing every hallmark: the pummeling ofdispossessed and besieged peoples by an overwhelming military power in the name of self-defenseand ‘western civilisation and values;’ the demonology and language of savagery, zoology andbestiality; the devaluation of life in racial taxonomies that actively produce disposability as thecondition of value elsewhere; the presentism and the refusal of any claims of a historical past orhistorical injustice. All of these areimmediately recognisable to millions of people in the world, notsimply as the persistence of a common past and history but also as the ominous sign of an imminentfuture on a warming planet that we are again being told is ‘overpopulated’.

Nadine Fraczkowski

Nadine Fraczkowski

Palestine, inthis sense, is the living archive of our future. But it is also the name of a renewedplanetary consciousness. It has been the cause for the largest global student movement ingenerations, the biggest manifestations of left internationalism the west has seen in decades, andprobably the largest mobilisations of Jewish anti-Zionist activism America has ever seen. These gainshave not been won despite Palestine’s war of liberation butbecauseof it; without the challenge ofPalestine’s anticolonialism, without the ability to upend the colonial logic of rule and refuse theentire imperial arrangement, all of this would be a moot point. None of the diplomatic, legal orideological gains would have been made without the armed struggle ensuring there was stillsomething on the ground worth fighting for.

This too is Zionism’s impasse. Its utter dependence on imperial patronage has never been clearer.But so too has its function as both moral-ideological and geopolitical-military pillar of a crumblingUS-dominated imperial capitalist order, and the genocidal extent to which that order will go to keepthat function operative. The stakes of the conjuncture, then, are global and could not be bigger–Palestine is everywhere because it names a political subject of radical universal emancipation.16 IfZionism has come to stand in for the ‘rights’ of settler colonialism and ethnonationalism everywhere, that is for the rights to close any kind of reckoning with ongoing colonial injustice and dispossessiveviolence anywhere in the world, then Palestine’s war of liberation today carries the anticolonial ideaglobally. If Zionism has become one of the points that brings together (and exposes the deep elective affinities between) late liberalism and late fascism, then Palestine carries the task of not justrenewing the common heritage of the left’s revolutionary history where no one else will, but alsobringing it into lived time, into the ‘time of initiative’. It is at once an awful and beautiful weight tocarry.

Notes

- Frantz Fanon,The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 40.

- Mahmoud Darwish, emory for Forgetfulness, trans. Ibrahim Muhawi (Berkeley: UC Press, 1995), 11.

- Joseph Massad, ‘Why Israel’s savagery is a sign of its impending defeat’,Middle East Eye,16 April 2024.

- Martin Shaw, ‘Palestine in international historical perspective on genocide’,Holy Land Studies9:1(2010): 1–24.

- al–Jazeera, ‘Civilians sheltering inside a Gaza school killed execution–style,’ 13 Dec 2023, https://www.al-jazeera.com/program/newsfeed/2023/12/13/civilians–sheltering–inside–a–gaza–school–killed–execution.

- Seraj Assi, ‘Israel’s horrific massacre at Gaza’s largest hospital’,Jacobin, 3 April 2024.

- Forensic Architecture, ‘Attacks on aid in Gaza: Preliminary findings’, 4 April 2024, https://forensic–architecture.org/investigation/attacks–on–aid–in–gaza—preliminary–findings.

- Mouin Rabbani, ’Israel mows the lawn,’London Reviewof Books, Vol. 36 No. 15, 31 July 2014.

- Samera Esmeir, ‘To say and think a life beyond what settler colonialism has made’,Mada Masr, 14 October 2023, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2023/10/14/opinion/u/to–say–and–think–a–life–beyond–what–settler–colonialism—has–made/.

- Bikrum Gill, ‘Two logics of war: Liberation against genocide’,EbbIssue 1, January 2024.

- Achille Mbembe, ‘The society of enmity’,Radical Philosophy200, Nov/Dec 2016, 25.

- Abdaljawad Omar, ’Can the Palestinian mourn?’Rusted Radishes, 14 December 2023, https://www.rustedradishes.com/can–the–palestinian–mourn/.

- Steven Salaita, ‘Down with the Zionist entity; long livethe “Zionist entity”’, 23 May 2024, https://stevesalaita.com/down–with–the–zionist–entity–long–live–the–zionist–entity/.